2020: The Year of Death ☠

How COVID-19 changed my opinion on death

My wrist lights up with a seering pain.

I can barely feel my hands anymore. My fingers lack dexterity; they feel weak. As I contract my left pinky, it moves with delayed speed. An aching sensation pierces through my upper back.

What’s going on with me? , I ask myself. Why did my body suddenly turn weak and slow? The only change had been the boxing and intense practice sparring sessions with my new roommate… and sure, my wrists felt sore the next day… but this?

I go through all the possible autoimmune diseases:

- ALS

- MS

- Severe Arthritis

I think back to this morning regretfully. After all, I did wake up to a call from the geneticist this morning.

She got to the news rather slowly.

After some testing… we’ve confirmed that you do, in fact, have the 1B variant

Pseudohypoparathyroidism 1B. – a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by misaligned knuckles (also known as Albright’s syndrome).

But that wasn’t the surprise; I already knew I had an autoimmune condition requiring me to take copious amounts of calcium carbonate supplements every day. The surprise was that I didn’t have the 1A variant but the 1B variant.

I consider the significance of my death. If I died right now, would I be OK with that? Hell, would it even matter 🤔…?

Everything has a timer.

The song we listened to; the enjoyment from the mouth-watering meal we just ate; the video we started watching on YouTube but never finished. If things didn’t have an end, then how could we have highs and lows?

Even COVID-19. Secure ourselves in our homes for long enough, let the virus run its course, or let the virus kill off hundreds of thousands of people and eventually, there will be no more people to infect (a la “herd immunity”).

But something else has a more important timer:

Us.

If 2020 has shown us something, it has alerted us to our fragility — and how easily we crumble in the face of a pandemic — of death. In the wake of COVID-19 and the former protests related to police brutality, “anti-mask-wearing”, or “black lives matter”, death has become the “hot topic”. We can try to ignore all the people around us, keeping our distance and wearing face masks, but it only adds insult to injury.

Eventually, we will die.

As a result, in 2020, we’ve become scared of death. Perhaps we have always feared death, but now it seems more apparent than ever in the wake of a raging pandemic.

We try to ignore death in our lives. We scorn those who point out the inevitable, shaming them for making us feel bad about our lives. We want to live our lives as safely as possible, in the illusion that we will live forever. Nothing has made this more clear than the COVID-19 pandemic; it only took seeing hundreds of people crying out for others to take the virus seriously in stretchers for people to take the idea of their lives ending seriously.

The ideal vision from Western media has taken over the world, giving rise to ideas like “white privilege”, the “American Dream”, fenced houses, guns, and protective measures to prevent malicious intent. It seems that in a self-dubbed “post-COVID” era, we’ve taken even more effort to ensure our own safety, to prevent death, and to deny others their identities in favour of our own. What ever happened to a life of minimalism, of trust, of safety, and of giving?

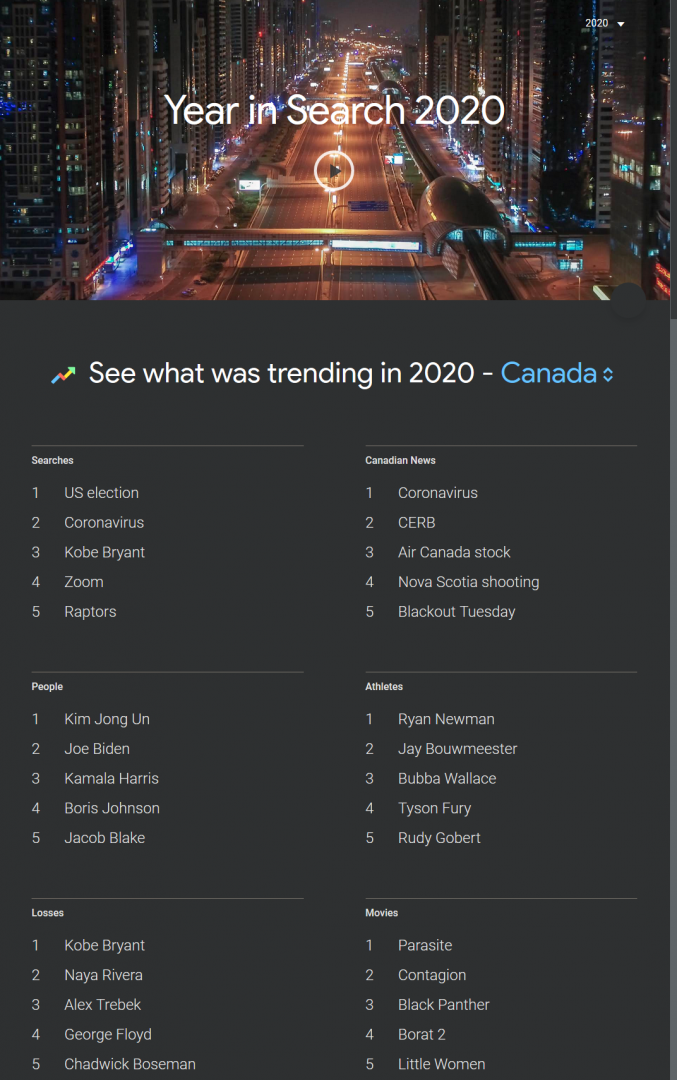

It’s easy to look to the media for answers when we only have our own selves, locked inside. With the swipe of a finger, we easily find ourselves staring in front of yet another screen — almost instinctively. From Google to Facebook to the suggested readings on the library of curated content from Apple, an answer to our woes most certainly exists. And even if it doesn’t, we’ll find it. In a very narcissistic way, Google has become the place where we look to affirm our beliefs; just look at the 2020 Google Trends.

When we don’t know what to do, we reach to technology to calm ourselves, to give us guidance, and yet the technology only seems to drive us further from our goals. What we really want is to free ourselves of our obligations, from our ideals that we’ve developed. We want to place ourselves in a fantasy world of non-commitment, one where our actions have no consequences. Some of the more educated may label this freedom from outcome, to have unique own values — ones not pedalled to us by the media and by the countless feeds of friends’ cool lives. And stuck at home, without any means of developing existential meaning in the world outside our home, we look to any form of self-preservation to provide that world to us: one of habit and non-social distancing.

Instead, what if we made time for ourselves, to live and breathe in the moment? What if we took out all the distractions we’ve put in place in our lives, took out everything that doesn’t make our lives great. What would we have?

Sigmund Freud writes about the unease caused by worrying about the past and future in his book Civilization and Its Discontents.

Suffering comes from three quarters: from our own body, which is destined to decay and dissolution, and cannot even dispense with anxiety and pain as danger-signals; from the outer world, which can rage against us with the most powerful and pitiless forces of destruction; and finally from our relations with other men.

Sigmund Freud

In Ekhart Tolle’s book, The Power of Now, Ekhart argues that concerns with the past and future only place unnecessary burden on us, and that instead, we ought to only focus on the now.

Realize that the present moment is all you ever have. Make the now the primary focus of your life. Whereas before, you dwelled in time and paid brief visits to the now, have your dwelling place in the now and pay brief visits to [the] past and future when required to deal with the practical aspects of your life.

Ekhart Tolle, The Power of Now

Ekhart goes on to argue that the dire state of civilization has arisen as a result of the denial of the present.

This collective dysfunction has created a very unhappy and extraordinarily violent civilization that has become a threat not only to itself but also to all life on the planet.

Ekhart Tolle, The Power of Now

The concept may not feel new to those exposed to Buddhism or East-Asian philosophy. Even in Mandarin, no specific “past tense” exists and must be determined by the time that the event happened (that an event happened in the past or future comes from context).

However, given our unpreparedness for the COVID-19 pandemic, doesn’t that indicate that we, if anything, did live in the now?

I think back to a conversation with some colleagues in the lowly-lit room in my basement suite, one of my coworkers chuckling lightly:

The funny thing about the Spanish Inquisition; they didn’t see it coming

Esteemed colleague

In his book, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, Jordan B. Peterson argues that we constantly live in a state of inadequacy, always seeking to improve.

We are always simultaneously at point A (which is less desirable than it could be), moving towards point B (which we deem better in accordance with our explicit and implicit values). We always encounter the world in a state of insufficiency and seek its correction.

We live within a framework that defines the present as eternally lacking and the future as eternally better.

Jordan B. Peterson

That we constantly yearn for something better reminds me of existentialism, some of which my dad often quoted to me in my years studying Jean-Paul Sartre in High School.

To be is to be

Jean-Paul Sartre

That the mind and overthinking death causes unease makes sense, but I have a hard time accepting that our aversion to death has resulted from overthinking things — the past and present. Nonetheless, Ekhart Tolle’s words echo in the back of my head:

What could be more insane, than to oppose life itself which is now and always now.

Surrender to what is. Say yes to life — and see how life starts working for you rather than against you.

Ekhart Tolle, The Power of Now

What if we have conditioned ourselves so that death comes as as surprise? What if we have put in place so many distractions in our lives that we no longer think about death? I think about all of this as I sit in my small basement suite, plagued (ironically) by the idea that a switch to minimalism might involve a lot more than just a post about it. A post like this will surely involve a deep introspection to modern-day culture, Eastern philosophy, and to human nature.

Death. Thousands upon thousands of people have died from COVID-19; in the U.S. alone this year, at least 216,000 more people died. Here in Canada, the numbers only continue to increase.

Yet, as I look down at my quaint setup of three wide-screen LCD monitors and a state-of-the-art desktop computer, I can’t but help to feel privileged. Not half a year ago, I found myself in Wuhan, China, followed by Milan and Turino, Italy — some of the hardest-hit places only months later.

To say I lucked out would be an understatement. Only earlier this summer, I nearly died — three times.

In a matter of months, the world transformed from simple to chaos. I witnessed the transformation as a bystander first, through countless video feeds from my friends in China, then through my hometown, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Stores closed down, preventative measures became enforced, restaurants closed, all culminating in mandatory lockdown. Within a matter of months, something as simple as grocery shopping became a large undertaking.

We live in a society where death seemingly has no place. We talk about death like a “virus” that kills, not to confuse it with the “deadly virus” of COVID-19 plaguing our Twitter and RSS feeds. Every day, we check the feeds for some reassurance that one of our loved ones won’t be next on the hit list. We really don’t want to have to face death; the prospect of dying in an uncontrolled way, at the behest of a virus we didn’t anticipate, irks us.

And yet all of us will die at some point.

Rightfully so, we don’t want our loved ones to die. It seems more than obvious that we want our families and loved ones to survive the pandemic. But through all our efforts to “slow the curve”, many will die — thousands more even. Have we really taken into account all these innocent peoples’ lives and their death wishes?

Take, for example, Guyaquil, Ecuador: one of the hardest-hit cities on the equator. Thousands of families quickly saw elderly die, and with no where to dispose of the bodies, the dead bodies got scattered on streets.

If it isn’t already clear, 2020 marks the year of death. We haven’t seen a pandemic like COVID-19 since the Spanish Flu in 1910. Many people have died, and will continue to die. This all begs the question: how can we help these people prepare for death?

While the number of COVID-19-related deaths do seem to be decreasing outside North America, the lack of PPE in many countries (including Canada) means transmission of the disease still has potential to trigger a second outbreak. Already, here in Canada, stores have started stocking essentials in the wake of a second wave.

Furthermore, limited ventilator access means that, like in Italy, doctors will have to decide “who gets to live” and “who gets to die”. This all begs the question of what to do when a COVID-19 victim’s life cannot be saved due to ventilator unavailability.

All of this begs the question of whether 2021 will offer any more than this last difficult year.

The death of one man is a tragedy; the death of millions is a statistic.

Joseph Stalin

During the 1930s, at the peak of his power, Joseph Stalin reportedly spoke about how numbers skew our perceptions of death. As general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1922 to 1952, he led a gruesome political regime, killing millions. He eschewed any moral obligation to his people’s lives by turning to statistics instead of developing empathy.

To Joseph Stalin, numbers of people weren’t people; they were numbers.

Political leaders, faced with decisions for masses of people, can’t develop empathy by very nature of their jobs; political leaders, instead, have the task of seeing the bigger picture, required to make life-or-death decisions for masses of people. As soon as political leaders separate situations on a case-by-case basis, they can no longer make any decisions. Of course, most political leaders fail at this, often at the whim of a mere public outcry (our two Michaels).

Tasked with making important life-or-death decisions for millions, such as the development of a vaccine, political leaders have to adopt an unbiased viewpoint — one that favours re-election or tries to make them look good in the public eye. Ultimately, for political leaders, decisions inevitably result from numbers and statistics. In the end, having empathy really plays a small part, if any.

We just happen to get caught up in it — consumed by the day-to-day statistics of COVID-19 cases diagnosed in our area –, inundated with charts, bar graphs, and diagrams from news outlets to make us scared. In a matter of months, we change the topic of discussion about the severity of the virus to raw statistics or deaths and bar charts. Worse, we look for reasons to find these numbers. We want to find reasons to excuse our poor physical distancing behaviours. As creatures of habit, the idea of distancing makes us question our purpose, so we look for any reasons to disobey the distancing measures enforced by authorities.

I can’t but reason that complete impartiality is impossible; regardless of any valiant efforts to take into account the thousands of deaths resulting from COVID-19, no amount of personal stories or struggles will suffice to develop sufficient empathy. While we can’t have a perfect point of view, we can strive to convey just how much a lost life means. What kind of life did the deceased live? What kind of life did they have ahead of them? Perhaps instead of speaking about the COVID-19 pandemic in numbers, in statistics of “cases diagnosed per day”, we might do better to investigate the complications these patients face. What would our outlook on the pandemic look like if we considered the severity of cases rather than blanket numbers, conveying little to no meaning on the lives of the infected.

Perhaps Joseph Stalin had it right after all: perhaps we do lose our empathy in the face of death, in our selfish quest to survive at all costs. Perhaps in the face of death, all common-sense goes to the wayside — no different than myself grasping on to a morsel of stone, imagining my imminent death.

But can we really justify such rash decisions on the outcome of peoples’ lives? Should empathy have a place when the fight against the coronavirus seems like a “free-for-all” anyway?

I wonder about all this, and more, considering the ramifications to come in this devastating year of 2020, where death seems to have grasped the world more than ever before.

The Meaning of Death

Reflection on death never benefited anyone to a large degree. What good does it do to “waste” time thinking about the inevitable? I think back to an anecdote of my logic professor in University who recanted a story about his partner rushing him in the parking lot to get to an event . “If we can’t walk any faster than we do now, then her idea of admonishing me to hurry is the perfect example of illogical”. In the same way, how does worrying about something we can’t change make any difference?

But we often forget one important, crucial detail: sometimes, we can walk faster. Sometimes, we don’t fully know our capabilities or what we can accomplish. Sometimes, it only takes a global pandemic to expedite the development of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Studying music in University, the concept made sense to me. The musician knows that thinking about missing notes only leads to missed notes, that trying not to make mistakes probably only leads to more.

And yet, it seems strange that we enjoy such a thrill when we face the prospect of death. How exciting it feels to jump off the diving board, and yet it feels even more so when we take a second to look down at the distant ground. How exhilarating it feels to look down a jagged cliff, knowing that one step could end everything we know.

Except we don’t look down at the possibility of death; our egos do.

We’ve built up an idea of how we should behave in our lives, mannerisms and behaviours we believe others expect from us through social conditioning. Our egos beg us to maintain an unscrupulous level of consistency, lest we fall to the mercy of death.

Death.

It seems that when we look adversity in the eyes, it scares us immensely at first, but the longer we take to contemplate our next actions, the more our indecision causes our egos to waver. Like the man telling the woman she looks pretty; like the employee asking for a raise, like myself staring my death in the eyes. It seems that the more we hesitate, the more inaction takes hold on us. What happens if she insults me? What if they fire me because I asked for a raise?

Only when we finally take the plunge into the unknown do we enjoy an immense sensation of euphoria — a feeling of excitement and passion so intense we just as quickly rise once again to take the plunge to the unknown. The thrill of life excites us, but very few of us actually stop to think about what makes this so. What if, perhaps, life retains such value because of death?

According to Alan Watts and other scholars, dating back to as far as Confucianism, such an idea isn’t too far off.

Life cannot exist without death; yin cannot exist without yang.

Perhaps the discomfort of thinking about an end causes our distrust in the idea of death. The thought that all our “efforts” in life will have gone to waste, that we may as well have not existed in the first place. Of course, this kind of thinking seems all too reminiscent of fatalism, or even the cynical outlook many millennials have adopted amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet without one another, we would not experience this thrilling sensation.

Just as Kongzi retorts to his disciple in the Confucian Analects:

Confucian Analects

“You do not understand life. How can you possibly understand death?”

Death & Loss

If we accept death as a crucial part of life and let go of our expectations of the past and future, how can we deal with loss? After all, some might argue that death and loss go hand-and-hand; even matriarch elephant females have been documented to linger around their dead offspring, fending off predators, mourning.

In other words, mourning is not unique to humans.

This begs the question: how should we cope with loss? When we lose our job, when a loved one dies; when we find out our home will become foreclosed; when we get denied admission at an institution. Do we jump at the first occasion to make a selfish release and to dump the sadness onto our close friends? Do we ignore the loss and pretend it never happened? Perhaps we turn to a guilty pleasure: ice cream, watching comedies, or maybe even drugs or alcohol.

A part of me wants to admit that shelving our misfortune on others does not help, but research shows it does. Rather, perhaps it makes more sense to look back to our previous state of abundance in a light of gratitude, thankful for what we had. Such an approach seems easy, but I know that making the best of a bad situation poses significant challenges when in a negative mindset.

Finding Abundance

Given the hundreds of thousands of deaths due to COVID-19 in 2020, it may seem hard to have any kind of positive outlook. So how can we ever find abundance after a year of terrifying daily death counts? Even ethically, how can we ever forgive ourselves for making light of such a serious situation?

The concept of finding abundance despite the terrifying outlook many face and will face in the coming years makes me shudder; I know it ethically wrong to feel good when everyone else around me feels bad, countless deaths happen every day, and many suffer… and yet, I can also reaffirm that my happiness is independent to me. Surely, those around me will also benefit from my happiness despite the pandemic.

I must equally acknowledge that such a mindset could justify evil, so I tred carefully in my path to self-enlightment during this terrifying pandemic.

However, hidden in the euphemisms we employ to dull the pain of death, traces of human nature form our relationship with death. Survivalism, at its core, seems to resonate with most religions, and yet when it comes to death, we make every effort to shame the dying.

Perhaps we should ask ourselves: did we have anything to lose to begin with? Ekhart Tolle might argue that we really do not have anything; instead, we only have the present.

Though capitalism — at least in the Western world — has steered us towards a materialistic lifestyle, favouring enhancement after enhancement, losing a material item pales in comparison with the loss of a life itself.

As humans, we have grown aversive to the unknown, to fear. We evolved to favour quick fixes, to stay in place. Death never helped us to propagate our genes and to reproduce. So we developed a system that labels it as taboo, hushing those who speak of it. Only in the past thousand years have we evolved away from a nomadic society to a sedentary one.

The very topic of death quickly became taboo in western culture. Through our evolution, we grew entitled to ownership, of entitlement. Somehow, some way, we disillusioned ourselves to believe that we are entitled to life.

But are we?

What if, instead, nothing ever belonged to us; rather, we only attributed ownership through language?

Instead, what if we celebrated death? Could that, perhaps, lead to a mindset of abundance?

An article published in Time Magazine suggests we might better prepare for our deaths by writing a document when-i-die.md, a markdown file like a will, coordinating the distribution of assets. The article takes a more sombre, pragmatic approach towards its view on death, but perhaps we can use this document to reaffirm our state of abundance? Or, perhaps, it may also suit us to skip the will altogether as we really only have the present…

The idea of celebrating death seems counter-intuitive to me, but I can’t help but think back to my accomplishments in travel — many undocumented on this blog. From almost dying in the mountains to traipsing miserably through slippery mountain in Kazakhstan, that I have survived until now eludes me.

See the World through Contrast

Thinking about life and death to such a degree, I begin to wonder if the contrast between life and death really has any meaning. As in the Confucian Analects, how can we ever expect to understand death if we don’t understand life?

How can you possibly know death without first knowing life?

Kongzi, Confucian Analects

What if, instead, the world does not operate in zeros and ones. Rather, we see the world in a binary way due to evolutionary biology?

In his book 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, Dr. Peterson argues that the differentiation and separation of objects results purely from evolutionary biology, citing examples such as:

- Hot or cold

- Good or bad

- Success or failure

- Pain or suffering

More recent studies have shown that our visual cortex has evolved over time to facilitate this task — of identification. As Dr. Peterson puts it:

Our minds are built on the hunting and gathering platforms of our bodies. […]

Jordan B. Peterson

Could life and death also fall into this category?

Language has evolved to outline contrast in our everyday lives — not to identify seemingly meaningless details like the spaces between. What would hot mean without knowing what cold means? What would the colour red mean to a colourblind person?

Science does no better than language. In his book The Order of Time, Carlo Rovelli demonstrates how Newton’s Laws of Physics all relate to our concept of distance measurement (the millimetre). However, the measurement actually corresponds to one person’s perception of the distance. The subsequent manufacturing of rulers and measuring devices adhering to this standard later aided the emergence of modern-day science. Yet very few of us stop to reconsider that our measurements all relate to one person’s perception of distance.

Only where there is heat is there a distinction between past and future. […]

The growth of entropy is nothing other than the ubiquitous and familiar natural increase of disorder. The difference between past and future does not lie in the elementary laws of motion, it does not reside in the deep grammar of nature; it is the natural disordering that leads gradually less particular, less special situations.

[…]

The difference between past and the future refers to only our own blurred vision of the world.

Carlo Rovelli

Thus, science, language, and all our perceptions only provide us understanding through contrast (the difference). What would it mean to have wealth if everyone else had the same amount of money? What would it mean to live forever if everyone else did? We almost certainly live our lives simply, without regard to the spaces between. But therein lies the problem: the spaces between subconsciously convey value to us.

In other words, the details are important.

When you get up in the morning and look at the room around you, what do you see? Do you see the inanimate objects: your bedside lamp, your phone, the paintings in your room, the wall? Or, do you see the negative space in between?

After all, what does identifying the negative space do for us?

Again, the problem.

That we look for purpose in everything we do says volumes about us. In some existentialist quest to define ourselves, we seek to avoid insanity and craziness by only furthering our lives’ objectives. For as Einstein once said:

Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, expecting a different result

Albert Einstein

And yet, as most of us confine ourselves to the insides of our homes, craving some form or routine, we do exactly what we set out not to do, consuming masses of media on our tablets, phones, telling ourselves a lie that “things will go back to normal” soon. It all most assuredly culminates in a feeling of desperation and anxiety — one easily mistaken for imposter syndrome.

In a very real way, we humans have become experts of deception and duplicity; we strive to maintain congruence in our everyday actions and yet, when faced with confinement and saving lives, we often first jump to save our own selves before others.

To understand the world, we must realize that the world comes together as a whole not from our own perceptions of it, but from our combined perceptions of the world. Our perceptions of death, of life, and everything in between. We tell ourselves a lie about the order of the world — that we have it all in order, that we will live infinitely long lives, and that we will prosper and become rich — some delusion of grandeur most certainly portrayed by mainstream media. We tell ourselves we can live the “American Dream”, but not once do we consider that having such riches would almost certainly not satisfy us.

In reality, the world doesn’t have an answer. We go searching for some idea of the meaning of life through our actions, never to complete our journeys. In fact, we almost certainly fail in the most miserable way because in many cases, we come out later on with more uncertainty than when we began our journey

Life is a Deception

To be is to deceive

Allan Watts

Like sweeping the dust under the carpet in a hurry just before the guests come, we fool ourselves into thinking the world has order when, in fact, the only order in life comes from the guarantee of death.

Think of camouflage: the chameleon changing its colour; think of the flower, bright and vibrant in colour, inviting the bee to pollinate; the virus’ two-week, asymptomatic incubation period. The world’s illusory nature fools us into thinking we have control, that we can somehow master the forces that control us. But the world doesn’t operate in zeros and ones; we can only understand the forces of nature, of viruses, and of pandemics through our best guess — science. Instead, we can observe life as it unfolds, not trusting in some benevolent system to guide us, but in ourselves.

Pain

The concept of pain irks most, and that comes as no surprise.

We don’t like pain. We avoid it at all costs. Hospitals, clinics, funerals, morgues, cemeteries … the list goes on of blatant euphemisms to cover up the associated pain.

Only now, it seems the media has touched the surface of what it might feel like to lose a loved one to a deadly virus. But even then, what shows up on the news feeds and TV screens is only numbers. In reality, we don’t want to hear the sob stories, the sad stories about the people lost; rather, we want affirmations that life will go back to “normal”, as if nothing happened. Like addicted gamblers, we flock to the media like religious followers, waiting to receive the fix — news that the virus’ toll has slowed, that we have finally won. Yet in an ironic twist, we developed these feelings of anxiety to confinement; we told ourselves that life without social distancing is like no life at all.

Most of us live our lives in search of pleasure — a noble pursuit pedalled to us by the media, by schooling systems, and by our friends. But most of us never stop and reflect on why we avoid pain.

Pain inherently relies on the duality and the separation of the feeling from the sufferer. After all, how could we possibly identify pain without understanding what it means to experience a lack of pain? Likewise, pain would have no meaning without some level of resistance from the sufferer.

Let’s Rethink Death

If our perceptions on life define how we see death, then we have an infinite canvas on which to change the way we see it in modern-day society.

Alan Watts puts it succinctly in his Essential Lectures:

There really isn’t anything wrong with being sick or with dying.

Who said you’re supposed to survive? Who gave you the idea that it’s a gas to go on and on?

We can’t say that it’s a good thing for everything to go on living in the very simple demonstration that if we allow everyone to go on living, we overcrowd ourselves. Like an unpruned tree.

Therefore, one person who dies is honourable because he’s making room for others.

Regardless of our efforts to suppress pain and suffering, life will go on.

Seeing the humanity in the pain and suffering can, instead, lead us to value our own fortune and health. Instead of suppressing the pain of the sufferer, we can, instead, opt to encourage the release and expression of discomfort.

Because in a world where thoughts and even remote references to death get covered up regularly with euphemisms, the spaces in between get blurred. Perhaps in an ironic twist, the disease from which we suffer lies within our incapacity to turn over the embroidery and to examine nature of suffering, pain, and death.

The Meaning of Life & Death

In such “challenging” times, guided only by countless misinterpretations of what we “should” do and how to pass the time in quarantine, it quickly becomes confusing to us how to spend our time in quarantine. Inevitably, as we scroll through the never-ending list of Netflix media to entertain us, we will ask ourselves what we aim to achieve with our constant entertainment — as if we ought to have more noble, genuine objectives like saving the world of a pandemic or of creating something “great” to benefit society.

This feeling largely results from not following feelings or ideas to their depth. Media tells us we want to be immortal, that we want to live forever, but do we really want to do that?

Think about it: what would a world look like without death?

The media has convinced us how to behave — imposed on us a set of beliefs based on material objects. In today’s world of Gucci handbags worth half the average person’s lifetime salary, Porches and watches designed only to convey status, the symbol of success has certainly eluded the daily lives of most of us. But how often do we really imagine what it would mean to us to have these things? What would you do with a large house all to yourself, an immortal life, an infinite reservoir of money? Would you live your life differently?

Likewise, if your government announced the end of quarantine measures, permitting you to end your quarantine immediately, would you live your life differently? Or perhaps would you stay at home?

Perhaps death does have a place. For as Kongzi replied to his disciple:

How can you possibly know death without first knowing life?

Kongzi, Confucian Analects